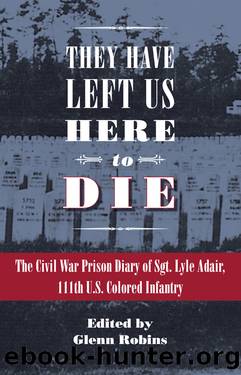

They Have Left Us Here to Die by Glenn Robins

Author:Glenn Robins [Robins, Glenn]

Language: eng

Format: epub

ISBN: 9781612779867

Barnesnoble:

Publisher: Kent State University Press

Published: 2013-01-20T00:00:00+00:00

CHAPTER 6

The Second Andersonville

ON DECEMBER 17, 1864, Gen. John Winder ordered the transfer of all prisoners from Thomasville to Andersonville.1 Just four days earlier, Gen. William Shermanâs men had captured Fort McAllister, a key defensive position some twelve miles south of Savannah, and begun preparing for a siege of the Georgia port city.2 Thus, with communication to Savannah severed and the railroad cut between Savannah and Thomasville, the trajectory of Shermanâs destructive march had forced yet another prisoner diaspora. This time the destination for the relocating prisoners was a known quantity, one with a horrific past; however, the prisoners soon discovered that Andersonville had developed a new identity.

The Andersonville story can be traced to late November 1863, when Capt. Sydney Winder received orders from J. W. Pegram, assistant adjutant general, to secure a site for a new prison facility in Georgia âin the neighborhoodâ of Americus or Fort Valley in the southwestern part of the state.3 After a month-long search, Captain Winder selected a spot a mile and a half from Station No. 8 on the Georgia Southwestern Railroad near Andersonville, a community with a population of fewer than twenty people.4

The proposed prison site appeared to be a sound choice because the area âwas heavily wooded with pine and oak, with the ground sloping down on both sides to a wide stream, a branch of Sweet Water Creek.â Local opposition impeded the construction process from the start and forced Confederate authorities to impress slaves and materials in order to begin the job. The original plan called for the construction of a prison of barracks capable of holding 8,000â10,000 prisoners. However, deteriorating conditions in Richmond and supply shortages at key production and logistical points throughout the South forced Confederate officials to radically alter the original plan. âIn desperation,â as historian Lonnie Speer has noted, âthe Confederate government ordered that a simple stockadeâin effect just a corral, the cheapest, most economical form of confinementâbe completed as soon as possible.â On February 25, the first prisoners arrived and entered the prison grounds, although the stockade had not been completed.5 The population grew steadily between February and May, with the four-month totals numbering 1,600, 4,603, 7,875, and 13,486, respectively. The average number of deaths per day for March, April, and May were 9, 19, and 23, respectively.6

For a variety of reasons, June marked a turning point in the tragic history of Andersonville Prison. On June 17, Gen. John Winder assumed command of the prison, replacing the first commandant, Col. Alexander W. Parsons. Winder, as the head of Confederate prisons in Georgia and Alabama, had ordered the appointment of Capt. Henry Wirz as commander of the interior of the prison. In mid-June, the two men faced an incredible task, as âthere were nearly 22,300 prisoners in the pen that was built for only half as many, and already more than 2,600 had died.â7 Indeed, as historian William Marvel explains, an exponential rise in the prison population occurred within a matter of a few weeks: âThe

Download

This site does not store any files on its server. We only index and link to content provided by other sites. Please contact the content providers to delete copyright contents if any and email us, we'll remove relevant links or contents immediately.

In Cold Blood by Truman Capote(3367)

The Innovators: How a Group of Hackers, Geniuses, and Geeks Created the Digital Revolution by Walter Isaacson(3119)

Steve Jobs by Walter Isaacson(2883)

All the President's Men by Carl Bernstein & Bob Woodward(2361)

Lonely Planet New York City by Lonely Planet(2206)

And the Band Played On by Randy Shilts(2183)

The Room Where It Happened by John Bolton;(2143)

The Poisoner's Handbook by Deborah Blum(2125)

The Innovators by Walter Isaacson(2095)

The Murder of Marilyn Monroe by Jay Margolis(2087)

Lincoln by David Herbert Donald(1979)

A Colony in a Nation by Chris Hayes(1915)

Being George Washington by Beck Glenn(1876)

Under the Banner of Heaven: A Story of Violent Faith by Jon Krakauer(1787)

Amelia Earhart by Doris L. Rich(1682)

The Unsettlers by Mark Sundeen(1679)

Dirt by Bill Buford(1665)

Birdmen by Lawrence Goldstone(1655)

Zeitoun by Dave Eggers(1636)